August 1, 2014

Profitability:

A rewards-first approach

BY MARK BRADLEYMaking consistent profits is critical. That’s not to say profit is everything. If you don’t have some passion for this industry, you’re not going to last. But, on the other hand, if your business isn’t making a consistent profit, then over time your passion will give way to frustration.

As a very small business — just you and a few helpers — it was much easier to exert control over destiny. You work hard, you work late, you know how much your jobs sell for and you have a good idea of how much time you can afford to spend before you need to move on to the next one. But as your business grows in size and staff, more and more owners lose touch with that connection to bottom-line results. Staff are paid hourly or by salary, and not by company success. Many have no idea what they should be selling and/or producing to be worth their wages. They put their head down and go to work. There’s little incentive to work harder, and there are very few quantifiable, objective goals to work towards.

If you want better staff, that has to change. Working without clear goals is like teaching someone to play the piano with earplugs in his ears! He hears muffled sounds, but he is never going to be any good. He can’t hear what it should sound like, and he can’t hear whether he is producing the right sounds, either. Without clear sound, it’s just banging the keys hoping it sounds good.

Goal-setting for sales and design

In a recent visit to a friend’s company, I found there was a disconnect between what the owner believed his sales staff needed to sell, and what his sales staff believed was realistic (and even possible). All parties are good, smart, talented people. They are going to go places. They just have different instincts on what they could realistically sell in a year.

So how do you bridge this gap? If you start from a rewards or profit-first mentality, the answers are as black and white as the text on this page. With some simple numbers that any company can get its hands on, we can make sure the sales goals directly correspond with the rewards for the individuals. For the owner, it’s net profit; for the designers, it’s their wages.

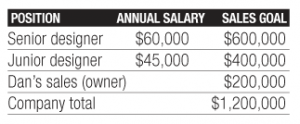

Let’s use our imaginary friend Dan to put some real numbers to this example. Dan would like to finish up the year doing about $1.2-million in design-build sales. He has two design/sales people. Dan sells some of the work, but he’d like to transition out of sales and is hoping his design staff can pick up the slack. One is more experienced than the other, and is better paid, so Dan assigns the following sales goals:

The figures look reasonable and add up to $1.2M, but are they right? Before we dive right in, we just need a few more (very) important numbers.

The figures look reasonable and add up to $1.2M, but are they right? Before we dive right in, we just need a few more (very) important numbers.The senior designer looks at Dan’s goal and says “Dan, I’ve never sold more than $500K before. I can’t do $600K.” Dan didn’t have a great year last year and he knows that’s never going to change unless his company sells more work. If anything, he thinks, it should be even higher! But neither one knows for sure. Until they turn to the facts.

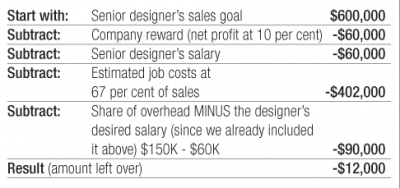

Let’s start with the senior designer’s sales goal and figure out who’s got it right.

Note: the numbers used in this article are realistic averages, but are intended for example purposes only. They should not be considered applicable to all companies. Know your company’s numbers.

STEP ONE: Budget the overhead

To be covered by the senior designer Dan’s company has $300K of overhead expenses for his design-build division. That’s a pretty realistic overhead budget for a company of his size. His designer’s sales goal is $600K, or exactly half of his total design-build sales goal of $1.2 million. It’s logical then to assign exactly half his overhead, $150K, to this senior designer’s jobs.

STEP TWO: Estimate cost of goods sold expenses

Dan’s costs to do the work (the costs of labour, equipment, materials, subs), on average, consume about 67 per cent of the selling price of the job. This is also in the normal range; 60-70 per cent Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) is typical of a successful design build company. For a successful maintenance company, 45 to 60 per cent is a typical COGS range.

You can estimate your own COGS percentage by dividing your total job costs (field wages + equipment + materials + subcontractor expenses) by your total sales. Note that different divisions can have very different averages.

With these numbers alone, we can easily determine if this design/salesperson is overpaid or underpaid, using our rewards-first process.

Uh-oh. We’re $12,000 short. Who’s going to eat that? Overhead is fixed, there’s nothing we can do about that. We can’t just cut job costs — we need those workers and materials. The company has to make a fair profit or we might as well close the doors. So what gives?

Uh-oh. We’re $12,000 short. Who’s going to eat that? Overhead is fixed, there’s nothing we can do about that. We can’t just cut job costs — we need those workers and materials. The company has to make a fair profit or we might as well close the doors. So what gives?The answer is simple. Using a rewards-first approach, this designer is worth an annual salary of $48,000. That will offset the $12,000 shortfall and everyone will be happy.

Except, of course, the senior designer! He will insist that he needs to make $60K! He’s got a family, kids and a mortgage. So, using our rewards-first approach, let’s set a goal that works.

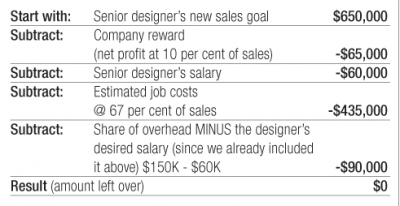

In the example below, I assume overhead remains fixed. Overhead costs won’t necessarily change if we increase our sales by a nominal amount, but they should be recalculated each year at a minimum.

Perfect. If our sales/designer wants to make $60K per year, his sales goal and the reasoning behind it is crystal clear, and it took about five minutes to get on the same page. The math does not lie. Hopefully, the very next thought in this designer’s head is “Wow. If could sell $900K, I could make $90K!”

Perfect. If our sales/designer wants to make $60K per year, his sales goal and the reasoning behind it is crystal clear, and it took about five minutes to get on the same page. The math does not lie. Hopefully, the very next thought in this designer’s head is “Wow. If could sell $900K, I could make $90K!” Now, repeat the same process for the junior designer so he understands what he is worth, and the sales he needs to generate to reach his desired income potential.

Of course, we need to make sure these estimates are accurate, and that the jobs are finished on budget. Next month, we’ll take a look at how to set production goals for foremen, with the same clear accountability to simple facts and numbers — and not gut instincts.

Mark Bradley is president of TBG Landscape and the Landscape Management Network (LMN), based in Ontario.